16-year-old Arnav reflects on the potential growth of Latin America despite corruption and internal violence

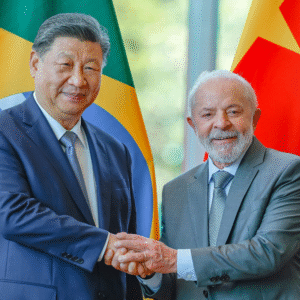

Chinese president Xi Jinping (left) and Brazilian president Lula Inácio Lula da Silva signed trade and development agreements in November 2024.

Picture by: Brazil Presidency | Alamy

Article link copied.

October 10, 2025

The promises, pitfalls and future of Latin America

Latin America is abundant in natural resources and cultural cohesion, yet hampered by corruption and uneven governance.

Stretching from Mexico through Central America and the Caribbean to the vast expanse of South America, it’s home to more than 670 million people. Common languages – Spanish dominates, Portuguese is widely spoken in Brazil – and shared traditions give the region a potential for unanimity.

This shared language, culture and membership of groups such as the Organization of American States (OAS) should give Latin America a strong voice on the world stage. But time and time again, the region has shown that having abundant resources is one thing – turning them into lasting prosperity is another.

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

A crash course in history

Two centuries ago, revolutionary leaders such as Simón Bolivar and José de San Martín fought to break the chains of Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule, inspiring a series of independence movements that reshaped the continent. Borders shifted, economies stumbled and power swung between populist leaders and military juntas. Commodity booms in coffee, copper and oil lifted economies, but inequalities and weak institutions left nations vulnerable.

By the late 20th century, instability mixed with a new threat: drug-trafficking. Narco violence and organised crime in Colombia, Mexico and across the Andes has left hundreds of thousands dead and eroded trust in institutions. The scars of the 1980s and 1990s still linger today.

Today, the region is charting a new path. Lithium fields in Chile; oil reserves in Venezuela and, more recently, in Suriname; and fintech (financial technology) startups in Brazil all signal emerging opportunities, while Costa Rica has long been a pioneer in sustainability and green growth.

Yet the contrast elsewhere is stark. Venezuela remains mired in collapse and totalitarianism; Haiti in political turmoil, with Port-au-Prince almost entirely (90%) controlled by armed gangs; and Nicaragua is under an authoritarian retrenchment under the rule of Daniel Ortega.

Why is Latin America stuck?

Considered the most biodiverse region in the world, Latin America has many advantages – plenty of land, plenty of culture and an abundance of resources to spare – but something still holds it back. Experts call this a “resource curse”.

Countries like Venezuela, rich in oil, and the ‘Lithium Triangle’ nations of Chile, Argentina and Bolivia, often see their vast reserves fuel corruption and instability rather than broad prosperity.

Corruption is one of the biggest roadblocks. In 2014, the Lava Jato (‘Car Wash’) anti-corruption probe in Brazil led to more than 360 convictions, putting top politicians and corporate leaders behind bars, including Marcelo Odebrecht, the CEO of Latin America’s largest construction firm and José Dirceu, a powerful figure in the then ruling Workers’ Party. But recently, Brazil’s Supreme Court has thrown out their convictions, and those of countless others, due to supposed “procedural problems” and “expired limitations”.

This systemic breakdown in accountability sets the stage for crime to thrive. Colombia’s big cartels – Medellín and Cali – officially collapsed years ago. But their fragments continue to control drug routes and influence communities. In Mexico, drug trafficking has rebounded as cartels such as the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Cartel dominate both the drug trade and local economies, with annual profits for Mexican cartels estimated between $25bn and $30bn.

Authoritarianism makes the situation even tougher. When leaders undermine democratic ideals, silence the press and cling to power through fraudulent elections, they also erode long-term economic confidence and drive away foreign direct investment (FDI). Nicaragua is a clear example of this. Daniel Ortega and his wife, Rosario Murillo, have concentrated power by proclaiming a shared presidency. A 64% average decline in FDI from 2018 to 2021 underscores how dramatically the Nicaragua’s economic appeal has declined in foreign markets.

Potential is potential

For all its setbacks, Latin America has clear paths to move forward. Much of this depends on how the region positions itself geopolitically, both inside and outside its own immediate neighbourhood.

India has begun to play a larger role in Latin America’s resource landscape. In 2024, India’s state mining company, KABIL, signed a $24m lithium exploration deal with Argentina. This year, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi oversaw a landmark agreement with Chile’s state mining company, Codelco, to secure long-term copper supplies for Indian firms. These moves signal how the region’s influence now stretches well beyond its traditional partners in Washington and Beijing.

China remains the dominant external player, pledging $9bnin new credit lines at the most recent summit between China and CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States) and backing it up with projects such as Envision Energy’s $1bn investmentin Brazil to produce sustainable aviation fuel from sugarcane.

Russia, though far less economically influential, has demonstrated considerable interest in energy imports; its state company Uranium One signeda $450m agreement to tap 23 million tons of lithium reserves in Bolivia.

Foreign direct investment trends underline the stakes. The region drew nearly $189bn in FDI in 2024, a 7% increase from the previous year.

Key players such as Brazil, Mexico and Argentina have received the lion’s share, but smaller countries are quietly reshaping the map: Guyana, a country of fewer than a million people, is projected to pump 1.3 million barrels of oil per day by the end of the decade, and Suriname is emerging as a new oil frontier, attracting interest from both American and Chinese energy firms eager to establish a foothold.

Alongside these shifts, NGOs and civil society groups have pushed for stronger safeguards, from Indigenous protests in Chile’s lithium sector to watchdog campaigns in Colombia, reminding investors that sustainable growth depends on more than resource wealth alone.

Regional organisations are another lever of influence. Mercosur (founded by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, and joined by Bolivia in 2024), is the largest trade bloc in Latin America and one of the largest in the world, representing 285 million people with a combined GDP of approximately $3tn.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Latin America’s future is still overshadowed by the weight of its challenges. Corruption, fragile institutions and creeping authoritarianism remain stronger forces than the reforms trying to contain them. In countries such as Venezuela, Haiti and Nicaragua, collapse and repression show how quickly progress can unravel.

Yet, signs of changes are emerging. Costa Rica and Uruguay prove that stability and long-term planning can deliver short-term results, while Guyana and Suriname show how even small states can reshape global markets with new oil wealth. Civil society across the region has grown louder, pushing for accountability and environmental safeguards. These efforts may not yet outweigh the entrenched problems, but they are no longer isolated sparks but something that Latin America as a whole progresses towards.

Some good is beginning to happen, and if it can keep growing – through stronger institutions, deeper co-operation, and shared lessons – Latin America may finally tip the balance towards lasting prosperity.

Written by:

Economics Section Editor 2025

Georgia, United States

Born in 2009, Arnav studies in Metro Atlanta in the United States. He is passionate about economics, investing, and finance, with plans to study economics at university.

Arnav joined Harbingers’ Magazine in October 2024 as a winner of The Harbinger Prize 2024 in the Economics category, earning a place in the Essential Journalism Course. During this time, while writing about the global economy, entrepreneurship, and macroeconomics, he demonstrated outstanding writing skills and dedication to the programme. His commitment earned him the position of Economics Section Editor in March 2025.

In his free time, Arnav holds leadership roles in finance-focused organisations at state and national levels and is the founder of a SaaS startup. He hopes to use his writing and leadership skills to contribute to social entrepreneurial efforts.

Arnav speaks English and Hindi fluently, with working proficiency in Spanish.

Edited by:

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism