16-year-old Lidya Gasper says the government must do more to promote Tanzania’s national language, Kiswahili

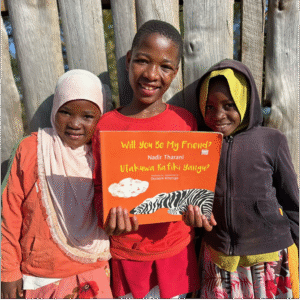

Children with a book in both Kiswahili and English.

Picture courtesy of: Dagmara Ikiert | Uvi Foundation

Article link copied.

July 4, 2025

Is English silencing Kiswahili in the Tanzanian education system?

I grew up speaking Kiswahili (also known as Swahili) in Tanzania, where it is the national language and a powerful symbol of unity. I spoke it at home, school, everywhere. To me, it is more than a language, it is a part of who I am.

But in 2023, when I started attending an international school, I quickly realised that English was given far more importance, dominating in the classroom and even in casual conversation with other Tanzanians. It started to feel like one country, two languages.

This experience made me wonder: is the Tanzanian government doing enough to promote the national language and protect our identity?

Harbingers’ Weekly Brief

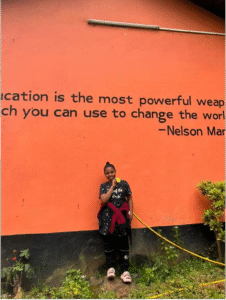

Lidya on her first day at international school.

Picture courtesy of: Dagmara Ikiert | Uvi Foundation

Kiswahili originated along the East African coast and is officially recognised in countries such as Tanzania and Kenya. It is also widely used in other countries including Uganda, Rwanda, Mozambique, Congo, Malawi, Zambia and Comoros. More than 230 million people speak it worldwide.

In Tanzania, more than 90% of citizens speak Kiswahili. It was developed in Bantu-speaking areas, but over time, it also absorbed vocabulary from Arabic, especially during the seventh century when Arab traders and settlers arrived on the coast. Through various interactions such as marriage, trade, cultural exchange and the spread of Islam, Arabic became integrated into the language.

After gaining independence from Britain in 1961, the Tanzanian government adopted Kiswahili and used it as the national language to promote unity and identity. The first president of Tanzania, Juliuse Kambarage Nyerere, played a key role in expanding the use of Kiswahili, especially in the education system and in government.

As a way of recognising the significant role that Kiswahili has played in bringing unity and cultural pride, in 2021 UNESCO declared 7 July as World Kiswahili Language Day.

English is too dominant

English was introduced and became normalised under British colonial rule during their control of Tanganyika – now Tanzania – from 1919 to 1961. The British established English as the language for governance and administration, while Kiswahili was left for local or informal use.

Over time, English came to be associated with access to higher education and better employment. This legacy continues to this day, creating a social divide where people who speak English tend to have greater socio-economic advantages, while those who lack fluency often face limited access to opportunities.

Although both English and Kiswahili are recognised in Tanzania, their roles are unequal. Kiswahili is taught in most government primary schools, but English takes over in secondary and higher education. This puts students from Kiswahili-based systems at a disadvantage, reinforcing inequality in a system that originated in colonial times.

Some assume that all Tanzanians naturally speak ‘pure’ Kiswahili, but in reality, some Tanzanian students may know English better, especially if their schooling or environment has emphasised English as the ‘better’ language.

In my experience, even though I am fluent in Kiswahili, I’ve often felt that real success depends on how much you speak English.

I think the government should invest in developing high-quality Kiswahili learning materials including translated textbooks in subjects like science, mathematics and geography. Teachers should also receive proper training in Kiswahili vocabulary and teaching methods.

To celebrate and preserve our linguistic and cultural identity, the nation should promote Kiswahili in national events by encouraging poetry (ushairi), drama (tamthilia) and storytelling (hadithi) in Kiswahili. Kiswahili Day should be marked with special celebrations that highlight the importance of the day and its role in the identity, unity and development of Tanzania.

To truly honour the vision of Mwalimu Nyerere (Mwalimu is Kiswahili for “Teacher”), Tanzania must do more to raise the status of Kiswahili – not just through words, but in practice. Equal access to education, opportunity and national participation should not depend on proficiency in a foreign language.

Kiswahili is more than just our language, it’s a part of our identity.

Written by:

Writer

Mtae, Tanzania

Born in Dar Es Salaam in 2009, Lidya Gasper graduated from Mtae Primary School and is currently attending an international school in Tanzania with plans to become a biologist.

She enjoys playing volleyball, dancing and studying. Her origins are in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania, and she has two brothers and two sisters. At Harbingers’ Magazine, Lidya is the Tanzania Correspondent. She describes the life of her community and shares her experiences.

She speaks Swahili and English.

Edited by:

🌍 Join the World's Youngest Newsroom—Create a Free Account

Sign up to save your favourite articles, get personalised recommendations, and stay informed about stories that Gen Z worldwide actually care about. Plus, subscribe to our newsletter for the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox. 📲

© 2025 The Oxford School for the Future of Journalism