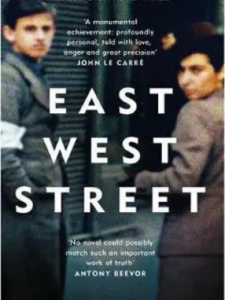

The notions of genocide and crimes against humanity are essential for international law and the efforts to protect human rights. In his 2016 book, East West Street, British writer and lawyer Philippe Sands explained the origins of these two notions.

The author focuses on the biographies of two Jewish lawyers from Lemberg – known as Lviv, Ukraine today – Raphael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht. They were born as the 20th century began – in 1897 and 1900, respectively – and became prominent during the Nuremberg Trials when they layed the foundation of the international criminal law system.

To write the book, Sands, himself a renowned international law expert of Jewish-Polish descent (his grandfather was born in Lviv) transformed into an archaeologist – his narrative takes the reader through the ruins of a train station, a vacant lot where a synagogue once stood, an abandoned storefront, and a former university campus and the site of a Nazi camp in Poland, where Jewish people deemed unfit for forced labour were sent. There, Sands unearthed the early beginnings of the arguments that would one day stop Nazi war criminals from using the example of British colonialism or the murder of African-Americans by the Ku Klux Klan in their defence. The protagonists of his book are depicted as unyielding advocates for justice, who fought tirelessly, and also with one another, to create a legal framework which still allows us to hope that war crimes, including genocide, and crimes against humanity, won’t go unpunished.

Simultaneously, he narrates the intellectual history which resulted in the creation of the notions of crimes against humanity (based on individual rights, it prioritises crimes against specific men and women) and genocide (which emphasizes crimes targeting specific populations or communities).